|

I am in the process of working on a new approach to an American History textbook on the collegiate level, which will tell a much broader story that includes not just wars, presidents and social history, but a significant amount of economics, political science, intellectual history et al. The first volume actually begins in 1400 and ends in 1500 -- just eight years after Columbus lands on San Salvador, accidentally sort-of discovering the Americas. It's necessary because students today have no idea of the world into which this country was born.

The individual segments are told in present tense (for the purpose of immediacy) and are each limited to 10 numbered paragraphs of no more than about 1,500 words total (so that students might actually read them). So here is the segment on Sir Arnold Savage, the man who engineered the principle that taxation was only legit when approved by the people and their representatives ... in 1404.

Because it is the second segment on English history in the book, it is important to know what the references to King Richard II mean. Henry IV deposed Richard II a few years earlier, imprisoning him in the Tower of London, where -- in 1400 -- he either starved himself to death out of spite (sure, that's likely), or was starved to death at Henry's order, or was murdered in more mundane fashion to get him out of the way (this was common). Having Richard II killed hurt Henry IV's reputation a lot, and then -- as if to add insult to injury -- Henry's enemies (which included the Catholic Church) started rumors that Richer had escaped and was still both alive and the real, lawful king. He wasn't, but as we have so often learned ... never let the facts get in the way of a good political narrative.

So, without further ado ...

|

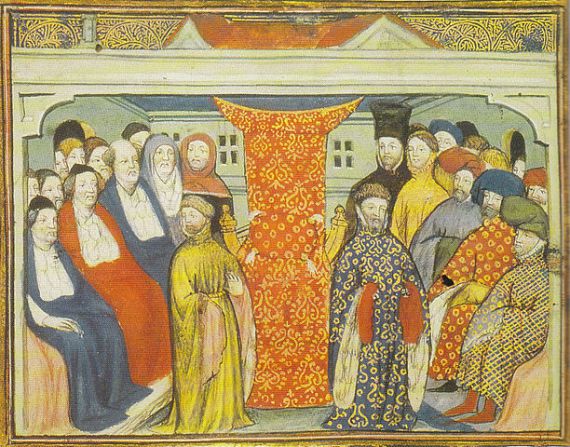

| Henry IV in Parliament -- he's in the fancy pajamas to the right of the central red tapestry. |

1404: The House of Commons, Parliament, London, England

1

Without studying history, we are left believing some really odd things. Here’s one: it is a fundamental principle with the US Constitution that the only legitimate mechanism of raising taxes on the people is for the people themselves, or representatives that the people themselves elect, to approve them. This is popularized in 1765 by Massachusetts attorney James Otis: “Taxation without representation is tyranny,” a saying that rivals Patrick Henry’s “Give me liberty or give me death” as the most important Revolutionary War meme. In more learned terms, the Stamp Act Congress declares that same year: “It is inseparably essential to the freedom of a people, and the undoubted right of Englishmen, that no taxes be imposed upon them, but with their own consent, given personally, or by their representatives.” This sentiment will also be fundamental in the Declaration of Independence just over a decade later, when King George III will be condemned for “imposing taxes on us without our consent,” and expounds on the concept of government “with the consent of the governed.” But what sounds like it is a right (perhaps God-given) that has existed forever, or is somehow inherent in the nature of society or the social contract, is really something that somebody has to first make up. Then they have to make it stick, which is what happens in England between about 1399-1404.

There are three ingredients necessary to take the power of taxation away from a king. First, you have to have a really weak king, who’s willing to make deals to keep that crown on his head. Second, you have to have some other emerging political and/or economic power other than the king and his lords--otherwise you just have rebellions and civil wars. Finally, you have to have someone who is agile enough to keep a foot in all camps at the same time, then move decisively at the right moment.

3

The weak king is Henry IV. Scotland threatens his northern frontier; the French are pushing against England’s remaining lands on the continent; Wales is in revolt. There are popular uprisings in the countryside, unrest in London and the larger towns. By 1403 there’s a civil war brewing between a group

of Yorkist lords and Henry IV’s Lancastrian following. The Royal Treasury is empty and huge loans are generating interest. The King has fallen ill, and appears fated never again to enjoy good health. Rumors spread across England that Richard II is still alive, and many local Church officials--the friars in the county parishes--become quite open in their scorn for the king, and in their desire that he be deposed. One of them, an elderly Franciscan friar named Roger Frisby becomes the spokesman when he and eight others are bound and dragged before the king.

4

HENRY IV: “These are uncouth men, without understanding. You ought to be a wise man. Do you say that King Richard is alive?”

FRIAR ROGER: “I do not say he is alive, but I say that if he is alive, he is the true king of England.”

HENRY IV: “He resigned!”

FRIAR ROGER: “He resigned against his will, in prison, which is against the law.”

HENRY IV: “He resigned with good will.”

FRIAR ROGER: “He would not have resigned had he been free, and a resignation in prison is not free.”

HENRY IV: “He was deposed!”

FRIAR ROGER: “When he was king, he was taken by force and put into prison, and despoiled of his realm, and you have usurped the crown.”

HENRY IV: “I have not usurped the crown, I was chosen by election.”

FRIAR ROGER: “The election is nothing, if the true and lawful possessor be alive today. And if he be dead, then he is dead by you, and if that be so, you have lost all right and title that you might have had to the crown.”

HENRY IV: “By my head, I shall have your head!”

FRIAR ROGER [as the bailiffs are pulling him away]: “You never loved the church, but always slandered it before you were king, and now you shall destroy it.”

HENRY IV: “You lie!”

A KNIGHT NEAR THE KING: “We shall never cease to hear this clamour of King Richard until the friars are destroyed.” (He’s right, it appears. Friar Roger is sent to the Tower of London, and the other eight friars with him have to be tried multiple times for treason until a jury can finally be found that will convict and behead them.)

5

During most of the Middle Ages, wealth in England is held primarily by the King, the nobles, and the Church. Most of that wealth consists of rural holdings: manors, villages, and farms. During the years between 1200-1400, however, English towns emerge as major economic and political powers. As trade expands (both within England and with other kingdoms) during the High Middle Ages, there’s a slow, steady shift of wealth from the great manors and farms to the bustling commercial fairs, the overseas merchant traders, and the guild-controlled controlled artisans including blacksmiths, goldsmiths, jewelers, farriers, weavers, and the like.

6

The towns also become a more important source of revenue for the King and his lords, but it is one they don’t really understand, though they dimly realize the towns’ wealth cannot simply be appropriated. Extracting taxes slowly becomes more of a transaction than a command. That is paralleled by an increase in the political power and independence of the towns, because that’s what they receive in trade for paying their taxes. Historian Alice Stopford Green explains that English towns have become nearly small independent republics: “The inhabitants defended their own territory, built and maintained their walls and towers, armed their own soldiers ... elected their own rulers and officials in whatever way they themselves chose to adopt … The townsfolk themselves assessed their taxes, levied them in their own way, and paid them through their own officers … They sent out their trading barges in fleets under admirals of their own choosing … and sent to the House of Commons the members who probably at that time most nearly represented ‘the people,’ that is so far as the people had yet been drawn into a conscious share in the national life.”

7

So: a weak King at odds with the Church, the country’s lords perpetually playing at bloody civil war, a royal treasury nearly empty, and bustling towns full of money they aren’t inclined to hand over to keep the elites living well. It’s a recipe for change that requires only one additional ingredient: leaders from the towns able to assert their (relatively) new power and make it stick. Enter Sir Arnold Savage, repeatedly elected as Speaker of the House of Commons (1400-1401, 1403-1404) and a member of the council that oversees the King’s finances.

8

Savage descends from minor Kent nobility; his family is closely associated with the faction of Edward III and Richard II right up until the moment Richard either starves himself or is starved to death in the Tower of London. Then Sir Arnold (a clever man, and an excellent speaker) rearranges his loyalties with surprising agility to become not only Speaker, but a member of Henry IV’s Council; while Henry perceives him as a critic, he never treats him as a traitor or a threat to the monarchy. This is both right and wrong: Sir Arnold does not particularly wish ill for the current King, but he does intend to trim back the power of royal power taxation.

9

In January 1404, Sir Arnold opens Parliament by telling everyone he’s not about to grant Henry IV any new money “until we know how the king’s wealth has been spent,” because “the king has sufficient wealth … if he would be well-guided.” Instead, he tells the King directly, “There are also certain lords of your council who lead and advise you with a very evil intention,” and that the only way the country can be governed (and that the King gets any more money), is “to order your affairs in the way that your [House of] Commons outline to your Council.” Under Savage’s leadership, the Commons refuses to grant the King any more money until he slashes his own household budget by 75%, removes all foreigners from that household, appoints a financial oversight council approved by Parliament, and manages the money through independent “war treasurers” responsible for seeing that funds collected for England’s armies are actually spent in support of the soldiers. Henry IV accepts this fiscal emasculation because it is the only way he can keep a crown on his head. He thus becomes the first monarch in English history to accept that the government may only lay taxes with the consent of the governed.

10

The interesting thing is that while this concept will become fundamental to the American understanding of government, in England it soon nearly disappears again. Sir Arnold dies in 1410, and so does King Henry IV in 1413, succeeded by his much stronger, successful son, Henry V. The Wars of the Roses throughout most of the 1400s make Sir Arnold’s gains in Parliament almost a dead letter. They continue to be mostly so under the even stronger monarchs of the Tudor Dynasty (1485-1603), while English towns slowly lose their political clout. But the idea--and the precedent--is there, simmering beneath the surface, waiting to re-emerge. When it does, sadly, nobody ever thanks Sir Arnold Savage.

Sources (for those who care):

Ian Mortimer, Henry IV: The Righteous King (Rosetta Books, 2014)

Parliament Rolls of Henry IV and Henry V (Constitution.org; n.d.); accessed April 16, 2020 at https://constitution.org/sech/sech_066.htm

UK Parliament/Parliamentary Archives, “Records of the House of Commons: Office of the Speaker” accessed April 16, 2020 at https://archives.parliament.uk/collections/getrecord/GB61_HC_SO

Faith Thompson, A Short History of Parliament, 1295-1642 (Minneapolis MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1953)

The History of Parliament, “SAVAGE, Sir Arnold (1358-1410) of Bobbing, Kent,” accessed April 16, 2020 at http://www.histparl.ac.uk/volume/1386-1421/member/savage-sir-arnold-i-1358-1410

Comments